TEN WEEKS AND COUNTING

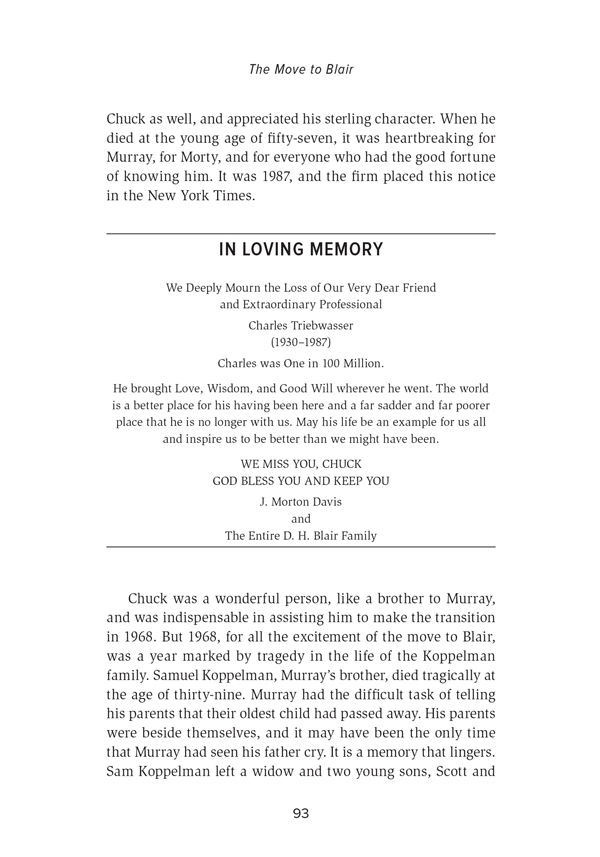

It was 1968, and though Morty Davis had originally called up Murray six years earlier to ask him to handle his personal tax returns, the biggest benefit to the firm of Triebwasser and Koppelman was doing the accounting work for D. H. Blair. Not only was Murray’s firm doing this business for Blair, but whenever Blair would do an initial public offering, it would recommend its clients use Triebwasser and Koppelman. This kept Murray and Chuck very busy. This time the call from Morty was a frantic one. It was not about his taxes or about a deal the firm was working on. Indeed, this call went to the very heart of the business of any broker dealer. In the late 1960s, the New York Stock Exchange had become very busy, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began to limit the number of trades that any firm could make in a given day to something like seven hundred. Sans computers, the volume was just overwhelming the agency. Having a flurry of activity is a great thing. But things had gotten so out of hand at Blair, and they were so busy that they did not know what actual securities they had or what they owed.

THE HAMMER, THE ANVIL, AND THE STREET

They needed help immediately. Without the situation being cleared up, there was a fear, whether real or imagined, that D. H. Blair would have to go out of business. Morty appealed to both Murray’s self-interest, Blair was Triebwasser and Koppelman’s best client, and to the personal friendship that they had developed. Murray is an out-of-the-box thinker, and such a challenge was right up his alley. He came to the Blair’s offices and surveyed the situation. Murray knew that the only way to reconcile the mess was to physically count every security. Doing this work on weekdays would mean impeding the firm’s normal

business, so he decided that the counting would take place on the weekends. The logical thing would be to have Blair employees come in on the weekends. But Murray knew that if they did that, not only would the staff be completely exhausted, but dealing with this very tedious work would dampen morale. He made the decision to hire people from other firms and have them work on the weekends, and he made sure to hire only accountants. He even rented out office space in another location. This job had to be done right. There was only one potential flaw in this grand scheme of Murray’s; the securities were held in a bank vault and banks are generally closed on weekends. Murray was not deterred, and when he called up the bank and apprised those in charge of his plan, they told him no can do. He asked them what it would cost to open the bank on the weekends. Whatever number they gave him was a bargain considering the stakes involved, and he gladly met their price. Not only did Murray hire about twenty people to go through the securities, and not only did he get the bank to open its doors to him on the weekend, he hired a slew of armed guards to watch it all. It must have been quite a scene that took place for ten weekends. Counting securities sounds a lot easier than it is. Every security has a serial number and a name. But many of the names are similar. Say you get a security in, and the name is Consolidated Railroad Ltd., but the security you expected in and failed to receive was named Consolidated Railroad Company. Both securities actually exist, but unfortunately you can’t replace one with the other, which would have made the situation much easier. The bottom line was that the enterprise was a disaster. After going through this ordeal of ten weeks, checking the buy and sell orders with the physical securities, Murray determined that there were about fifty or sixty breaks—discrepancies in the books—that they just couldn’t account for. Part of the complexity was that they were dealing with a hundred brokers, and the trades they were doing on their behalf were with many different firms. There was a variety of elements in play, and just one careless mistake and you are in a world of trouble. Two terms figured heavily into untangling the mess: Failure to deliver is a situation in which the buying broker does not receive the delivery of securities that he bought by the settlement date, three business days from the trade; and failure to receive

refers to the opposite scenario. Murray’s solution to the fifty or sixty breaks, in the case where you had a failure to deliver, was that you would sell the security in question. If there was a failure to receive, then you would buy it. In other words, you would absorb whatever loss or whatever gain resulted from the trade. But the end result should be is that everything balanced out. Of course, the real solution is something we call the computer, and that would come in time. Today, the paperless push and the electronic world that we live in mean that such certificates, and, one hopes, such difficulties as Murray faced, are becoming a thing of the past. But it was this crisis and Murray’s deft handling of it that would propel his career in a different direction.

THE DECISION

Morty Davis was understandably relieved by the outcome. His rise on Wall Street had been meteoric. He had become the top