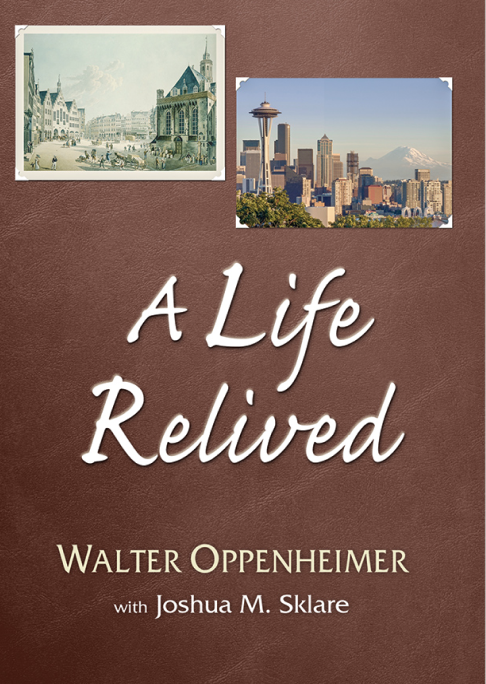

A Life Relived

By Walter Oppenheimer with Josh M. Sklare

Published: 2016, 165 pages

Client: Walter Oppenheimer

Born: June 25, 1923, in Frankfurt Germany Died: October 31, 2016, in Seattle, WA

Industry: Manufacturers’ Rep Firm

Nazis arrested Walter’s father during Kristallnacht in 1938 and the family was able to escape Germany. His family ultimately settled in Seattle, Washington. In 1940, Walter joined the Army and served in Alaska during World War II. He married, had children, and enjoyed a successful career as a manufacturers’ rep.

MY RETURN February 1998

It seemed to be just another typical cold and rainy winter day as I looked out the window of my sixth floor apartment. Though my Seattle apartment sits high atop the First Hill neighborhood, the morning’s grayness prevented me from seeing much of the city. However, despite the climate and the occasional lack of sunshine, the reader will quickly detect the strong affection I have for Seattle. It has been my home ever since I arrived here in 1940. As I do every day around noon, I took the elevator down to the lobby to retrieve the mail. Nestled in between a bill and a sweepstakes offering was an official looking envelope, with a postmark that was very familiar to me. It bore the stamp of Frankfurt, Germany. In haste, I opened it and found that it contained a letter from the city’s mayor inviting me to return to my birthplace as a guest of the city. Of course, the mayor was requesting my presence not because he was seeking my advice on urban renewal or any other matter relating to municipal governance. I was being invited to Frankfurt for one reason and one reason only: I was a Jew and as a result of the persecution levied against the Jews during the Nazi era, I had departed the city fifty-eight years earlier. And had I not left Germany together with my family in a most interesting journey that I will describe in these pages, I would have likely suffered the terrible fate that befell the vast majority of European Jewry. The invitation was part of a program that had been inaugurated in a number of German cities during the 1990s to bring Jews back to their hometowns and have them witness the many changes that have materialized in the four decades since the war’s conclusion. Of course, many former residents who had, like me, managed to flee or otherwise survive the war were nearly all senior citizens. Those who were sending out the invitations must have figured that either it was now or never. Guilt surely played a large part in their desire to welcome back their former residents and I, like all of the other invitees, had a major decision to make. Do I accept the city’s overture, or do I reject it? Some Jews have returned to visit Germany over the intervening years. They have come to visit and tend to the graves of their ancestors. Others have come because they wanted to show their birthplace and former residence, the streets that they played on as youngsters to their own children and grandchildren. Still others must have wondered what became of their city, town, or village. There have been those who adamantly declared that once they left Germany, they would never return. They believed that they could never step foot on the soil of a country whose citizens were capable of the horrors that we call the Holocaust. Many Jews had roots in Germany going back hundreds of years and despite all that the Jews had contributed to the country’s culture and economy, they became non-persons in the matter of a few years. Could you go back to such a country? My father, a man who always looked ahead and was never interested in dwelling in the past, had a very simple answer to this moral quandary. He sided with those who vowed not to return under any circumstances. Never a man to mince words, he once told me, “Once thrown out is enough.”

I can understand my father’s perspective. As tied as he was, by dint of birth, heritage, and culture to a Germany that he had once loved, he felt that once he left, and under the circumstances he left, that was it. The goodbye was final and everlasting. I realized that my returning could be interpreted as sending a message of absolution, forgiveness, or reconciliation. I explained the internal conflict that I had felt in an article about my experience of returning to Germany that appeared in the September 1998 issue of the Seattle Jewish Transcript. In it, I said, “You are invited to your hometown in Germany; should you go? The answer is yes and no. Yes, because you have a chance to tell students what happened during the Holocaust era. No, because it is too difficult to forget.” Why did I feel the responsibility to tell young people what had happened in their hometown and their country? The sentiments behind the famous words of philosopher George Santayana were a major incentive, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” And as the link with the past becomes ever fainter, as years and generations pass by as surely as night follows day, Santayana’s warning beckoned me to return. That the experiences of the Jews in Germany could go from a chapter in history to a footnote in it is something we all have a responsibility to prevent. So therefore I wrote to the Mayor’s office and indicated to them if they could arrange for me to speak at my old school, then I would accept their invitation. I felt that if my trip to Frankfurt could serve a positive, educational function in exposing today’s youngsters to the horrors of the past, then it would be a worthwhile enterprise. I received a positive response to my request and in June 1998 I got on a plane and returned to Germany.